Crisis Communication: A Quick Guide

While executives often cannot predict a crisis, they can expect that one will affect their company at some point. Proper planning and training will help companies respond quickly and appropriately when a crisis hits, mitigating potential damages.

Ayers Public Relations defines a crisis a critical event or period of time that can bring significant change, either good or bad. Crises may affect your financial stability or reputation. Recent acts of terrorism have sparked concern in American businesses, but crises can be much more routine such as lawsuits, layoffs and product recalls.

Crises can generally be separated in to two categories, surprise events and non-surprise events. A surprise event is anything “out of the blue,” like plane crashes, death of a key officer, fire or earthquake. A non-surprise event is one that management should have – or could have — foreseen, such as layoffs, mergers and lawsuits.

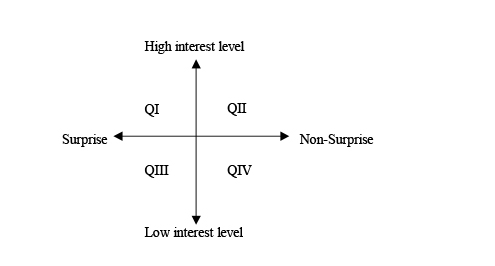

To help our clients rate the potential impact of a crisis and formulate a proper response, Ayers Public Relations developed a matrix to evaluate what we refer to as the crisis quotient. As shown below, the matrix contains one axis to rate whether the event is surprise or non-surprise, and a second to define the interest level or newsworthiness of an event.

The matrix is divided into four quadrants simply numbered one through four. Quadrants one and two represent the most potentially devastating type of crisis – those with high public interest. These are the events that will likely thrust your company into the media’s attention and if handled poorly, can keep it there. Situations like scandals, embezzlements, major recalls and sudden tragedy often can become newsworthy, regardless of whether they are a surprise or non-surprise event. Quadrants three and four represent events with lower interest level. The company’s crisis team typically can handle these quickly without sparking a media frenzy.

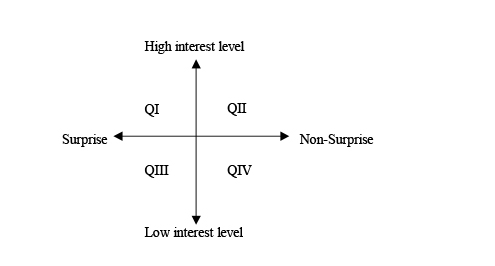

In addition to rating the type of crisis a company is facing, the matrix is an excellent tool to track the interest level of a crisis over time. In one of the most well-known crisis communications case studies, Johnson & Johnson handled the Tylenol tampering case masterfully and over a relatively short period of time decreased the national interest level in the disaster considerably, as shown in the graph to the right.

Conversely, and unforeseen event can push a low interest level event into the media spotlight, calling significant attention to a company. One example of this was a major airline that was laying off many employees. The airline attempted to keep the situation quiet by having employees call a hotline to learn about the layoffs. One of the affected employees called a local business news radio show and suggested they call the hotline. The radio show called the hotline, learned about the layoffs and then called the airline to find out more information. The airline representatives not only refused comment but also would not admit to the layoffs. The radio show continued to broadcast throughout their discovery process leaving the public with a bad image of the airline and elevating a potentially minor situation, as shown on the graph at right.

The interest level of a situation is influenced by the size of a company, the geographical scope of affected people or businesses — global, national or local, and whether or not the media is interested. The farther way media is from the situation, the lower the interest level is likely to be. For example, the New York Times is not likely to be interested in a small company in Colorado unless the company’s crisis impacts New York businesses and people. However, a crisis at large company in Colorado such as Miller Coors, Lockheed Martin or even Chipotle may be news in New York as it could impact businesses nationwide.

It’s never too soon to develop a crisis plan. Contact Ayers Public Relations today to find out how we can help you weather the storm should a crisis arise.

The matrix is divided into four quadrants simply numbered one through four. Quadrants one and two represent the most potentially devastating type of crisis – those with high public interest. These are the events that will likely thrust your company into the media’s attention and if handled poorly, can keep it there. Situations like scandals, embezzlements, major recalls and sudden tragedy often can become newsworthy, regardless of whether they are a surprise or non-surprise event. Quadrants three and four represent events with lower interest level. The company’s crisis team typically can handle these quickly without sparking a media frenzy.

In addition to rating the type of crisis a company is facing, the matrix is an excellent tool to track the interest level of a crisis over time. In one of the most well-known crisis communications case studies, Johnson & Johnson handled the Tylenol tampering case masterfully and over a relatively short period of time decreased the national interest level in the disaster considerably, as shown in the graph to the right.

Conversely, and unforeseen event can push a low interest level event into the media spotlight, calling significant attention to a company. One example of this was a major airline that was laying off many employees. The airline attempted to keep the situation quiet by having employees call a hotline to learn about the layoffs. One of the affected employees called a local business news radio show and suggested they call the hotline. The radio show called the hotline, learned about the layoffs and then called the airline to find out more information. The airline representatives not only refused comment but also would not admit to the layoffs. The radio show continued to broadcast throughout their discovery process leaving the public with a bad image of the airline and elevating a potentially minor situation, as shown on the graph at right.

The interest level of a situation is influenced by the size of a company, the geographical scope of affected people or businesses — global, national or local, and whether or not the media is interested. The farther way media is from the situation, the lower the interest level is likely to be. For example, the New York Times is not likely to be interested in a small company in Colorado unless the company’s crisis impacts New York businesses and people. However, a crisis at large company in Colorado such as Miller Coors, Lockheed Martin or even Chipotle may be news in New York as it could impact businesses nationwide.

It’s never too soon to develop a crisis plan. Contact Ayers Public Relations today to find out how we can help you weather the storm should a crisis arise.

The matrix is divided into four quadrants simply numbered one through four. Quadrants one and two represent the most potentially devastating type of crisis – those with high public interest. These are the events that will likely thrust your company into the media’s attention and if handled poorly, can keep it there. Situations like scandals, embezzlements, major recalls and sudden tragedy often can become newsworthy, regardless of whether they are a surprise or non-surprise event. Quadrants three and four represent events with lower interest level. The company’s crisis team typically can handle these quickly without sparking a media frenzy.

In addition to rating the type of crisis a company is facing, the matrix is an excellent tool to track the interest level of a crisis over time. In one of the most well-known crisis communications case studies, Johnson & Johnson handled the Tylenol tampering case masterfully and over a relatively short period of time decreased the national interest level in the disaster considerably, as shown in the graph to the right.

Conversely, and unforeseen event can push a low interest level event into the media spotlight, calling significant attention to a company. One example of this was a major airline that was laying off many employees. The airline attempted to keep the situation quiet by having employees call a hotline to learn about the layoffs. One of the affected employees called a local business news radio show and suggested they call the hotline. The radio show called the hotline, learned about the layoffs and then called the airline to find out more information. The airline representatives not only refused comment but also would not admit to the layoffs. The radio show continued to broadcast throughout their discovery process leaving the public with a bad image of the airline and elevating a potentially minor situation, as shown on the graph at right.

The interest level of a situation is influenced by the size of a company, the geographical scope of affected people or businesses — global, national or local, and whether or not the media is interested. The farther way media is from the situation, the lower the interest level is likely to be. For example, the New York Times is not likely to be interested in a small company in Colorado unless the company’s crisis impacts New York businesses and people. However, a crisis at large company in Colorado such as Miller Coors, Lockheed Martin or even Chipotle may be news in New York as it could impact businesses nationwide.

It’s never too soon to develop a crisis plan. Contact Ayers Public Relations today to find out how we can help you weather the storm should a crisis arise.

The matrix is divided into four quadrants simply numbered one through four. Quadrants one and two represent the most potentially devastating type of crisis – those with high public interest. These are the events that will likely thrust your company into the media’s attention and if handled poorly, can keep it there. Situations like scandals, embezzlements, major recalls and sudden tragedy often can become newsworthy, regardless of whether they are a surprise or non-surprise event. Quadrants three and four represent events with lower interest level. The company’s crisis team typically can handle these quickly without sparking a media frenzy.

In addition to rating the type of crisis a company is facing, the matrix is an excellent tool to track the interest level of a crisis over time. In one of the most well-known crisis communications case studies, Johnson & Johnson handled the Tylenol tampering case masterfully and over a relatively short period of time decreased the national interest level in the disaster considerably, as shown in the graph to the right.

Conversely, and unforeseen event can push a low interest level event into the media spotlight, calling significant attention to a company. One example of this was a major airline that was laying off many employees. The airline attempted to keep the situation quiet by having employees call a hotline to learn about the layoffs. One of the affected employees called a local business news radio show and suggested they call the hotline. The radio show called the hotline, learned about the layoffs and then called the airline to find out more information. The airline representatives not only refused comment but also would not admit to the layoffs. The radio show continued to broadcast throughout their discovery process leaving the public with a bad image of the airline and elevating a potentially minor situation, as shown on the graph at right.

The interest level of a situation is influenced by the size of a company, the geographical scope of affected people or businesses — global, national or local, and whether or not the media is interested. The farther way media is from the situation, the lower the interest level is likely to be. For example, the New York Times is not likely to be interested in a small company in Colorado unless the company’s crisis impacts New York businesses and people. However, a crisis at large company in Colorado such as Miller Coors, Lockheed Martin or even Chipotle may be news in New York as it could impact businesses nationwide.

It’s never too soon to develop a crisis plan. Contact Ayers Public Relations today to find out how we can help you weather the storm should a crisis arise.